Computer Network 读书笔记

- 2. Physical Layer

- 3. Data Link Layer

2. Physical Layer

3. Data Link Layer

Data link layer take the packet from network layer, and encapsulates them into frames for transmission. Each frame contains a frame header, a payload field for holding the packet, and a frame trailer.

Packet ---- Network Layer

|

v

| Header | Payload | Trailer | ---- Data Link Layer

3.1 Design Issues

Data link layer has following functions:

- Provide a well-defined service interface to network layer.

- Deal with transmittion errors.

- Regulate the flow of data so that slow receivers are not swamped by fast senders.

3.1.1 Service Provided to Network Layer

-

Unacknowledged connectionless service.

Used for low error rate channels, real-time services(e.g. voice).

-

Acknowledged connectionless service.

Used for unreliable channel (e.g. wireless systems).

The request-ack stuff done at data link layer is better than at network layer in this case, it is because links usually have a strict maximum frame length imposed by the hardware, and known propagation delays. The network layer might send a large packet that is broken up into, say, 10 frames, of which 2 are lost on average. It would then take a very long time for the packet to get through. Instead, if individual frames are acknowledged and retransmitted in data link layer, then errors can be corrected more directly and more quickly.

-

Acknowledged connection-oriented service.

Used for long, unreliable links such as a satellite channel or a long-distance telephone circuit.

3.1.2 Framing

The data get from Physical Layer is some kind of bit stream, Data Link Layer needs to break up the bit stream into frames. A good design must take it easy for the receiver to:

- Find the start of new frames.

- Use little of the channel bandwidth for framing.

Four methods are introduced:

-

Byte count

-

Description

Use a field in the header to specify the number of bytes in the frame.

-

Con

Bit flip in length field cause un-synchronization. The receiver even can’t know the start of next frame.

-

-

Flag bytes with byte stuffing

-

Description

Use a flag byte as both the starting and ending delimiter, shown as below:

| FLAG | HEADER | PAYLOAD | TRAILER | FLAG |There are cases that the payload contains the flag byte, in which case the sender need to stuff a same flag byte before it to escape, while the receiver should remoe the first flag byte if it encounter two contiguous flag bytes. This is called byte stuffing.

-

Con

This method is tied to the use of 8-bit bytes.

-

-

Flag bits with bit stuffing.

-

Description

The delimiter is now changed from a flag byte to a bit pattern (e.g. 01111110/0x7E). Whenever the sender’s data link layer encounters five consective 1s, it automatically stuffs a 0 bit at the end. When the receiver sees five consecutive incoming 1 bits, followed by a 0 bit, it automatically destuffs the 0 bit.

-

-

Physical layer coding violations.

-

Description

Add redundency to help the receiver. For example, in the 4B/5B line code 4 data bits are mapped to 5 bitss to ensure sufficient bit transitions. This means that 16 out of the 32 signal possibilities are not used. We can use some reserved signals to indicate the start and end of frames.

-

3.1.3 Error Control

Data link layer needs to ensure the frames are eventually delivered to the network layer only once.

-

ACK

For the acknowledged services, normally the protocal asks the receiver to acknowledge to the sender if one frame is correctly received or not. Then the sender will judge if need a resend.

-

Sender Timer

To avoid the sender’s from waiting forever for the ack (e.g. sender’s frame is lost in link, which means there will be no ack), the sender should start a timer once sending a frame. When timeout, it should send the frame again.

-

Numbered Frames

For the 2nd case, if the ack is lost in link, then the sender re-send the frame, which will cause the receiver to accept the same frame twice. To avoid this, it is necessary to assign sequence number to outgoing frames so the receiver could distinguish retransmissions from originals.

3.1.4 Flow Control

The data link layer needs to ensure a fast sender will not swamp a slow receiver. Two approaches are commonly used:

-

Feedback-based flow control (link layer and higher layers)

The receiver sends back information to the sender giving it permission to send more data, or at least telling the sender how the receiver is doing.

-

Rate-based flow control (transport layer)

The protocol has a built-in mechanism that limits the rate at which senders may transmit data, without using feedback from receiver.

3.2 Error Detection and Correction

There are two strategies for dealing with errors:

-

Error-correcting (Forword Error Correction, abbr. FEC)

By using error-correcting codes, the receiver is able to deduce what the transmitted data must have been.

(used on non-reliable channels)

-

Error-detecting

By using error-detecting codes, the receiver is able to deduce that an error has occured(but not which error).

(used on reliable channels)

3.2.1 Error-Correcting Codes

Four codes are mentioned:

-

Hamming codes

-

To reliably detect d errors, you need a distance d+1 code (i.e. distance between two closest leagle codes >= d+1 );

-

To reliably correct d errors, you need a distance 2*d+1 code.

(m+r+1) <= 2**r

Look here for the detailed calculation process.

-

-

Binary convolutional codes

Soft-decision decoding, could handle ‘uncertainty’ case.

-

Reed-Solomon codes

-

Low-Density Parity Check codes

3.2.2 Error-Detecting Codes

Three codes are mentioned:

-

Parity

A single parity bit is appended to the sent data.

If one block only has one parity bit, and there is long burst error garbling the block, then the probability of detecting the error is only 50%. We can regard each block to be a nxk rectangle, then we can either append one parity bit for each row (i.e. up to k bit errors) or interleave the parity bit for each column. In this case, we can improve the detection rate in long burst case (but still error-prone)..

-

Checksums

-

Cyclic Redundancy Checks (CRCs)

Check out the Painless guide to CRC.

3.3 Elementary Data Link Protocols

3.3.1 A Utopian Simplex Protocol

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

/* Protocol 1 (Utopia) provides for data transmission in one direction only, from

sender to receiver. The communication channel is assumed to be error free

and the receiver is assumed to be able to process all the input infinitely quickly.

Consequently, the sender just sits in a loop pumping data out onto the line as

fast as it can. */

typedef enum {frame arrival} event type;

#include "protocol.h"

void sender1(void)

{

frame s; /* buffer for an outbound frame */

packet buffer; /* buffer for an outbound packet */

while (true) {

from_network_layer(&buffer); /* go get something to send */

s.info = buffer; /* copy it into s for transmission */

to_physical_layer(&s); /* send it on its way */

} /* Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day

To the last syllable of recorded time.

– Macbeth, V, v */

}

void receiver1(void)

{

frame r;

event_type event; /* filled in by wait, but not used here */

while (true) {

wait_for_event(&event); /* only possibility is frame arrival */

from_physical_layer(&r); /* go get the inbound frame */

to_network_layer(&r.info); /* pass the data to the network layer */

}

}

3.3.2 A Simplex Stop-and-Wait Protocol for an Error-Free Channel

This takes flow control into consideration for preventing the sender from flooding the receiver with frames faster than the latter is able to process them.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

/* Protocol 2 (Stop-and-wait) also provides for a one-directional flow of data from

sender to receiver. The communication channel is once again assumed to be error

free, as in protocol 1. However, this time the receiver has only a finite buffer

capacity and a finite processing speed, so the protocol must explicitly prevent

the sender from flooding the receiver with data faster than it can be handled. */

typedef enum {frame arrival} event type;

#include "protocol.h"

void sender2(void)

{

frame s; /* buffer for an outbound frame */

packet buffer; /* buffer for an outbound packet */

event_type event; /* frame arrival is the only possibility */

while (true) {

from_network_layer(&buffer); /* go get something to send */

s.info = buffer; /* copy it into s for transmission */

to_physical_layer(&s); /* bye-bye little frame */

wait_for_event(&event); /* do not proceed until given the go ahead */

}

}

void receiver2(void)

{

frame r, s; /* buffers for frames */

event_type event; /* frame arrival is the only possibility */

while (true) {

wait_for_event(&event); /* only possibility is frame arrival */

from_physical_layer(&r); /* go get the inbound frame */

to_network_layer(&r.info); /* pass the data to the network layer */

to_physical_layer(&s); /* send a dummy frame to awaken sender */

}

}

3.3.3 A Simplex Stop-and-Wait Protocol for a Noisy Channel

Protocols in which the sender waits for a positive ack before advancing to the next dasta item are often called ARQ(Automatic Repeat reQuest) or PAR(Positive Ack with Retransmission).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

/* Protocol 3 (PAR) allows unidirectional data flow over an unreliable channel. */

#define MAX SEQ 1 /* must be 1 for protocol 3 */

typedef enum {frame_arrival, cksum_err, timeout} event_type;

#include "protocol.h"

void sender3(void)

{

seq_nr next_frame_to_send; /* seq number of next outgoing frame */

frame s; /* scratch variable */

packet buffer; /* buffer for an outbound packet */

event_type event;

next_frame_to_send = 0; /* initialize outbound sequence numbers */

from_network_layer(&buffer); /* fetch first packet */

while (true) {

s.info = buffer; /* construct a frame for transmission */

s.seq = next_frame_to_send; /* insert sequence number in frame */

to_physical_layer(&s); /* send it on its way */

start_timer(s.seq); /* if answer takes too long, time out */

wait_for_event(&event); /* frame_arrival, cksum_err, timeout */

if (event == frame_arrival) {

from_physical_layer(&s); /* get the acknowledgement */

if (s.ack == next_frame_to_send) {

stop_timer(s.ack); /* turn the timer off */

from_network_layer(&buffer); /* get the next one to send */

inc(next_frame_to_send); /* invert next frame to send */

}

}

}

}

void receiver3(void)

{

seq_nr frame_expected;

frame_r, s;

event_type event;

frame_expected = 0;

while (true) {

wait_for_event(&event); /* possibilities: frame_arrival, cksum_err */

if (event == frame_arrival) { /* a valid frame has arrived */

from_physical_layer(&r); /* go get the newly arrived frame */

if (r.seq == frame_expected) { /* this is what we have been waiting for */

to_network_layer(&r.info); /* pass the data to the network layer */

inc(frame_expected); /* next time expect the other sequence nr */

}

s.ack = 1 − frame_expected; /* tell which frame is being acked */

to_physical_layer(&s); /* send acknowledgement */

}

}

}

3.4 Sliding Window Protocols

For bidirectional communication via one link, each frame’s header could contain a kind field indicating if the frame is data or ack.

-

piggybacking

Improvement of above scheme. When data frame arrives, instead of immediately sending a separate ack, the receiver restrains itself and waits until the network layer passes it the next packet. The ack is attached to the outgoing data frame (using the ack field in the frame header).

It is not always the case receiver should wait. The receiver should start a timer to wait for next packet from network layer. If the new packet arrives quickly, the ack is piggybacked onto it. Otherwise, if packet arrived by the end of this time period, then data link layer just sends the separate ack to sender side.

-

sliding window protocol

The sender maintains a set of sequence numbers corresponding to frames permitted to send. These are frames that have been sent or can be sent but are as yet not acked. Whenever a new packet arrives from network layer, it is given the next highest sequence number, and the upper edge of the window is advanced by one. When an ack comes in, the lower edge is advanced by one.

The receiver maintains a set of sequence numbers corresponding to frames permitted to receive. When a frame whose sequence number is equal to the lower edge of the window is received, it is passed to the network layer and the window is rotated by one. Any frame falling outisde the window is discarded. In all of these cases, a subsequent ack is generated to the sender.

3.4.1 A One-Bit Sliding Window Protocol

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

/* Protocol 4 (Sliding window) is bidirectional. */

#define MAX SEQ 1 /* must be 1 for protocol 4 */

typedef enum {frame arrival, cksum err, timeout} event type;

#include "protocol.h"

void protocol4 (void)

{

seq_nr next_frame_to_send; /* 0 or 1 only */

seq_nr frame_expected; /* 0 or 1 only */

frame r, s; /* scratch variables */

packet buffer; /* current packet being sent */

event_type event;

next_frame_to_send = 0; /* next frame on the outbound stream */

frame_expected = 0; /* frame expected next */

from_network_layer(&buffer); /* fetch a packet from the network layer */

s.info = buffer; /* prepare to send the initial frame */

s.seq = next_frame_to_send; /* insert sequence number into frame */

s.ack = 1 − frame_expected; /* piggybacked ack */

to_physical_layer(&s); /* transmit the frame */

start_timer(s.seq); /* start the timer running */

while (true) {

wait_for_event(&event); /* frame arrival, cksum err, or timeout */

if (event == frame_arrival) { /* a frame has arrived undamaged */

from_physical_layer(&r); /* go get it */

if (r.seq == frame_expected) { /* handle inbound frame stream */

to_network_layer(&r.info); /* pass packet to network layer */

inc(frame_expected); /* invert seq number expected next */

}

if (r.ack == next_frame_to_send) { /* handle outbound frame stream */

stop_timer(r.ack); /* turn the timer off */

from_network_layer(&buffer); /* fetch new pkt from network layer */

inc(next_frame_to_send); /* invert sender’s sequence number */

}

}

s.info = buffer; /* construct outbound frame */

s.seq = next_frame_to_send; /* insert sequence number into it */

s.ack = 1 − frame_expected; /* seq number of last received frame */

to_physical_layer(&s); /* transmit a frame */

start_timer(s.seq); /* start the timer running */

}

}

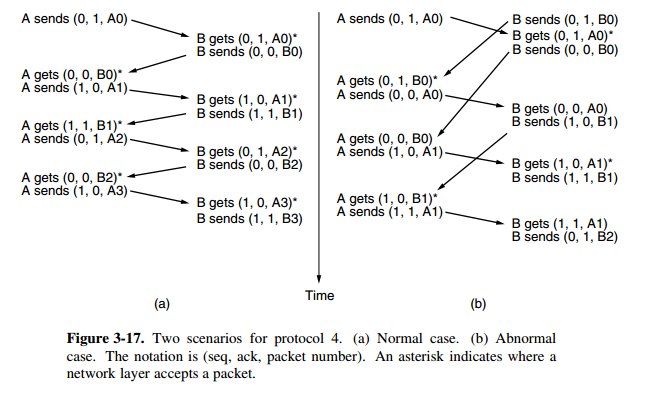

Under normal circumstances, one of the two data link layers goes first and transmits the first frame. In other words, only one of the data link layer programs should contain the to physical layer and start timer procedure calls outside the main loop. As shown in situation (a).

If A and B simultaneously initiate communication, their first frames cross, and the data link layers then get into situation (b). In (a) each frame arrival brings a new packet for the network layer; there are no duplicates. In (b) half of the frames contain duplicates, even though there are no transmission errors. Similar situations can occur as a result of premature timeouts, even when one side clearly starts first. In fact, if multiple premature timeouts occur, frames may be sent three or more times, wasting valuable bandwidth.

3.4.2 Go-Back-N

Last protocol has low efficiency on bandwidth usage. After improving the bandwidth usage by allowing the sender to tranmist up to w frames before blocking (instead of 1) for ack. The theoretical w equals to 2*BD+1, where BD equals to: bandwidth * one-way transit time / bits per frame.

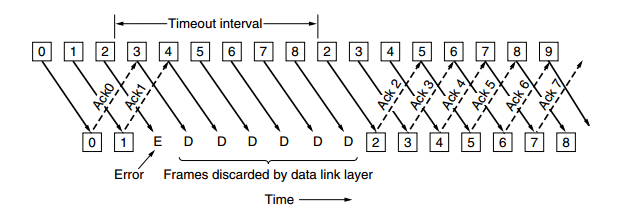

This method has a serious issue. If a frame in the middle of a long strem is damaged or lost, large numbers of succeeding frames will arrive at the receiver. Two basic apporaches are available to deal with these errors, one is the go-back-n (described in this section), the other is called the selective repeat (described in next section).

go-back-n is for the receiver simply to discard all subsequent frames, sending no ack for the discarded frames. This strategy corresponds to a receive window of size 1. In other words, the data link layer refuses to accept any frame except the next one it must give to the network layer. If the sender’s window fills up before the timer runs out, the pipeline will begin to empty. Eventually, the sender will time out and retransmit all unacknowledged frames in order, starting with the damaged or lost one. This approach can waste a lot of bandwidth if the error rate is high.

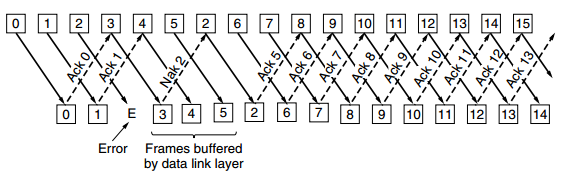

3.4.3 Selective Repeat

The other general strategy for handling errors when frames are pipelined is called selective repeat. When it is used, a bad frame that is received is discarded, but any good frames received after it are accepted and buffered. When the sender times out, only the oldest unacknowledged frame is retransmitted. If that frame arrives correctly, the receiver can deliver to the network layer, in sequence, all the frames it has buffered. Selective repeat corresponds to a receiver window larger than 1. This approach can require large amounts of data link layer memory if the window is large.

Comments